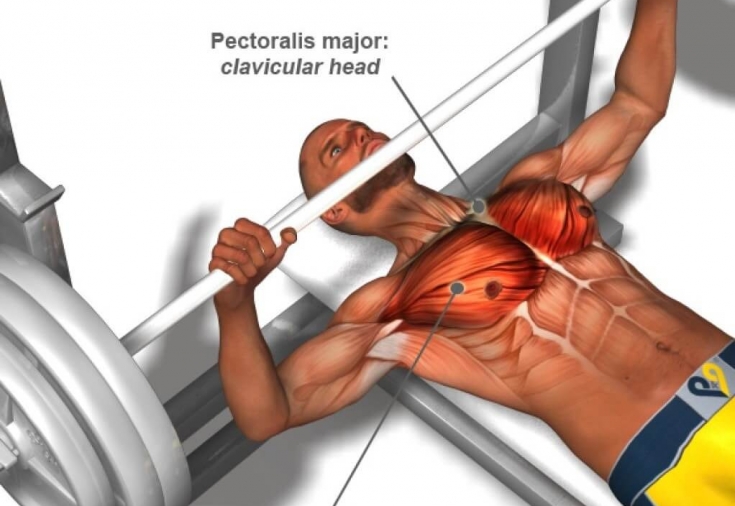

Experts agree: queuing for the bench is the best kick-off to your week

Spend enough time in gyms, and you notice there’s always a line for the bench press stations on Monday. Every meathead, it seems, wants to start his week by working his chest. Spend enough time writing about strength training, as I do, and you find yourself making lots of arguments for why that’s a bad idea.

Among them:

- The chest is only one of your major muscle groups, and has less mass than your lats, glutes, and thighs.

- Overtrain your chest and you risk shoulder injuries that could force you to stop training it altogether.

- Lower-body exercises like squats and deadlifts will do more to improve your performance in just about every sport.

- Women like a well-proportioned guy.

Then I read a 2009 study titled “Formidability and the Logic Of Human Anger,” and I realised the guys lining up at the bench press station on Monday had it right all along. Or, at least, they’re more in touch with their primal selves than I am.

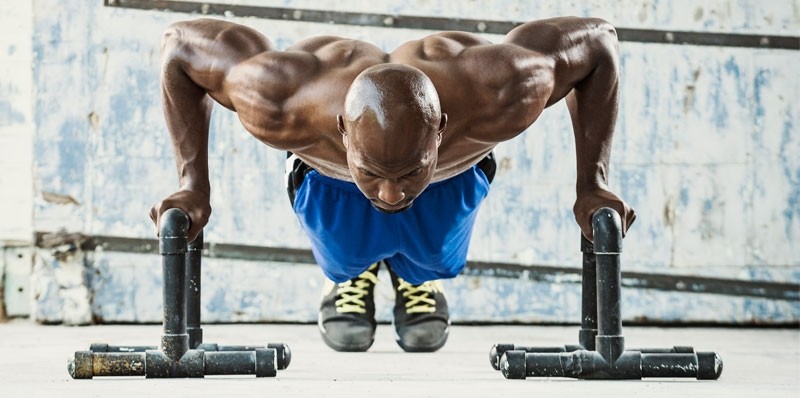

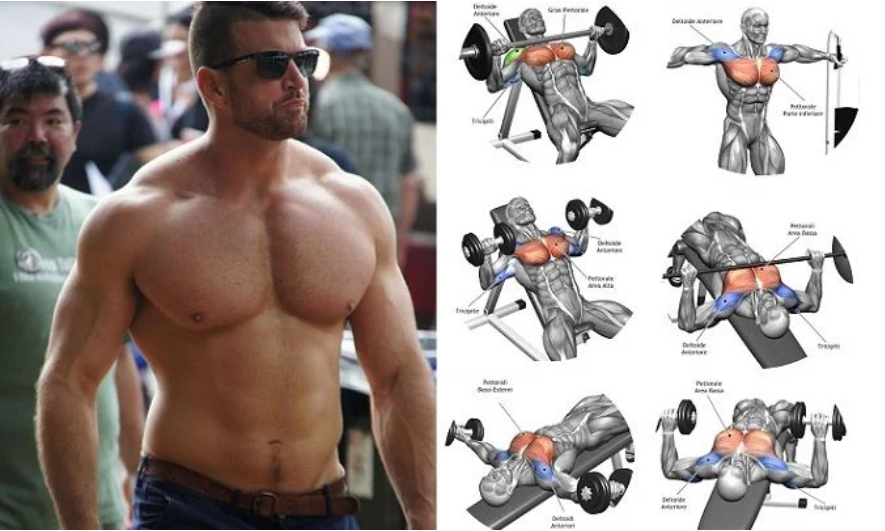

The study found that guys who are judged to be more “formidable” by others are quicker to get angry, and more likely to get what they want because of their anger. “Most men, and boys for that matter, want to be formidable,” says Aaron Sell, Ph.D., a criminologist at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and the study’s lead author. “Upper-body strength in particular is more closely related to fighting ability, and when people are asked who is strong and shown photos of men, they pick the men with upper-body strength.”

Sell’s research has spanned the globe, from college students in Southern California, Argentina, and Denmark to Native Americans still living close to the land in Bolivia. The patterns hold in every group studied: men who are perceived to have the most upper-body strength are assumed to be the most formidable, which is to say the most capable of winning a fight.

Why does that matter in a world like ours, where the average guy is more likely to get scammed by a Nigerian prince than forced into hand-to-hand combat? To find the answer, we have to go back to the world that existed for most of human history.

Basic instincts

Before we outsourced our hunting to Trader Joe and our fighting to the UFC, an average guy had a high chance of dying in battle. Even in contemporary hunter-gatherer societies, violent confrontations account for as many as one-third of all male deaths.

So it makes perfect sense that all of us – men and women – have highly evolved instincts for judging which guys pose the biggest threat to our safety, or might be the best ally in a brawl. Sell’s studies show that upper-body strength is a better proxy for fighting ability than height, weight, or lower-body strength, and we assess it in multiple ways, including facial and vocal cues.

Our assessment of our own upper-body strength, and by extension our potential to intimidate others, tends to be as accurate as those of the men and women we encounter. It doesn’t matter if we actually try to use the advantage; we all know it’s there because we literally size each other up all day, every day.

Even babies know they should let the Wookie win. In a 2011 study inScience, researchers showed that year-old, preverbal infants understand that little things need to get out of the way of big things, and show surprise when the opposite occurs.

This follows them all the way up the developmental ladder. “You don’t have to teach children that when they win a sports game, they should feel good,” Sell says.

As adults, we have lots of ways of keeping score, but the most primitive one still matters. “Natural selection designed men to detect upper-body strength, and use that estimate when deciding whether they can take another person in a fight, or win a conflict against them,” Sell says.

Which explains the magnetic pull of the bench press. We’re hard-wired to want to be bigger and stronger than the next guy, and to make sure he knows it.